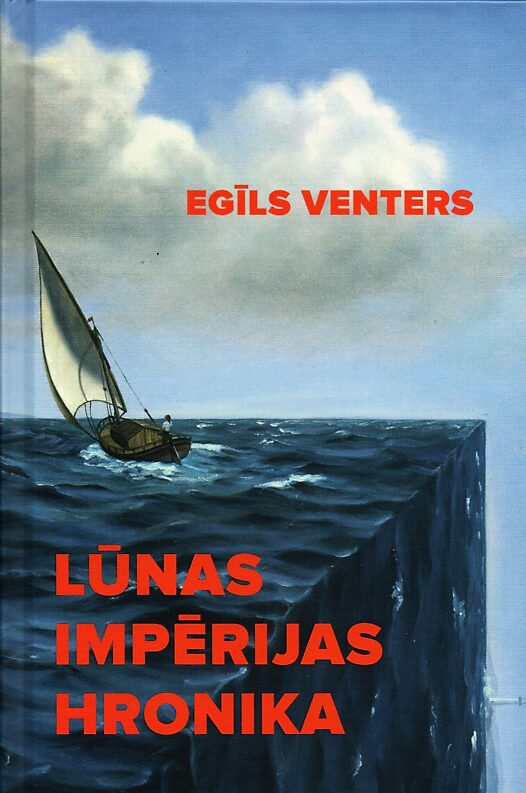

A

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LUNA EMPIRE

1.

Amaru’s

father was the island’s penultimate ruler; everything that happened during his

rule was what Plato later called the “nature of the gods interfering with the

nature of man” and the “inability to survive true happiness.” It was during his

rule that the entertainment empire was created, which they called LUNAparks—gambling

halls, strip clubs, gladiator battles, and everything else that came to the

isolated island from the continent.

In his better years, his father

was a thickset man with a round Moon face; the fire symbol in the middle of his

forehead was like one of Luna’s craters and was the ideal source of inspiration

for the court poet to write the an ode in praise of the “eternal ruler.”

2.

It

was also during his father’s rule that Zeus decided to punish the degenerate

human race, even though the reason wasn’t the fall of mankind, as the eschatologists

like to think. What really angered Zeus was his visit to the Amilos Province.

There, unbeknownst to him, the god was served human flesh. As revenge, the

ruler of Olympus turned the ruler of Amilos into a wolf—so that he himself

would have to eat human flesh.

Zeus battered the Amilos palace

with ferocious lightning; it seemed that would be enough for the gods, but it

wasn’t certain.

The gods of Olympus met and

unanimously agreed to wipe out mankind—by sending upon them a terrible storm

with earthquakes and torrential rains.

After us, the deluge, was the

most commonly heard phrase that summer.

3.

In

Amaru’s memory, his grandfather was a monumental gray-haired man with thick

eyebrows and a bad set of dentures. He was a monument among monuments; you

couldn’t throw a rock without hitting something dedicated to the great Successor,

a pyramid or bust; Poseidon and Luna had more dedications, but none of them

were as grand as the orichalcum pole erected in his grandfather’s time, which

was engraved with words specially chosen by the court poets; they were engraved

with golden words into the pole:

“Our ruler is a spirit of the

earth, who appears at nightfall and shines like lightning in the broad expanse

of night.”

An anonymous historian had

something else to say about this era:

“The sun hid behind the clouds

all summer long. There was complete silence across the land; a thick fog

covered the people and fields like a sail. The air was heavy and oppressive;

the people had no happiness or joy.”

This is the time of Amaru’s

childhood.

4.

Amaru’s

grandfather is better described in another ancient Greek record:

“The entire world looks like a

field of corpses. A red evening glow—the blood of those sentenced to death. The

stars—the scattered bones of the dead. A bright moon—a skull.”

This era was known as the Great

Fire or the Great Terror, but his grandfather—a sneering, bearded man with a

pipe between his lips—inspired fear in everyone from Tyrrhenia in Europe to the

land on the other side of the sea.

And it was he who introduced the

concept of TWO WORLDS.

5.

In

reality, the ancient Greek myth about Athena’s and Poseidon’s quarrel has

immortalized the memory of the Greek-Atlantean war. This myth doesn’t say

anything about the reasons for the war, or that the islanders’ seaside sunsets

as well as sunrises were red—but that even the Moon rose bloody.

Two-thirds of Asia’s population

was killed in the name of the Luna Empire, as was three-fourths of Europe’s

population. The bearded ruler also wiped out half of the island’s population,

who were slow to realize that the sign of the Sun had no room in their lives.

The thousand-years-old Sun cult

was reduced to rubble in less than a decade.

Once he’d finished with the

islanders, his grandfather turned to Europe and Asia.

6.

The

Athenians pushed the Atlantean forces back to the sea, and forced them to

retreat to the island. Since that war (which, let’s remember, the bearded ruler

referred to as the TWO WORLDS WAR), no ship fared the sea between the continent

and the island, except for on moonless nights.

Herodotus believes that the Atlantean

lost the war (which was the real first world war) because the Athenians and

Asians DIDN’T worship the Sun, and because many of their gods were similar to

those of the Atlanteans.

The Luna Empire showed its

weakness for the first time, and thousands of warriors returned to the island,

ashamed.

Their hearts retreated into the

shadows of doubt—was the Moon a false god?

Translated by Kaija Straumanis